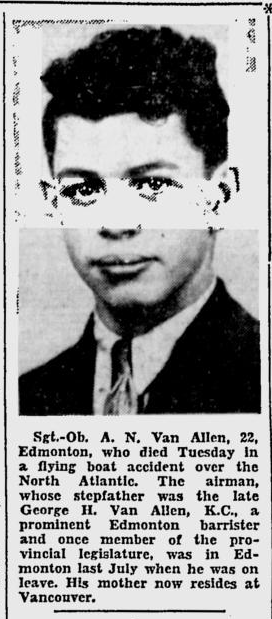

February 24, 1921 - September 9, 1941

![]()

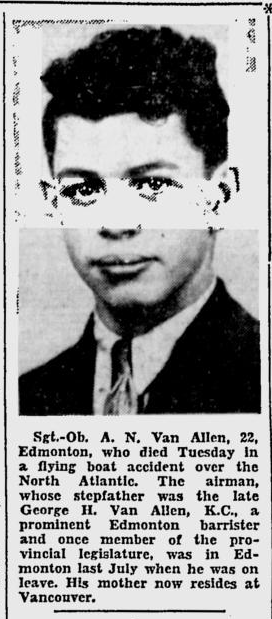

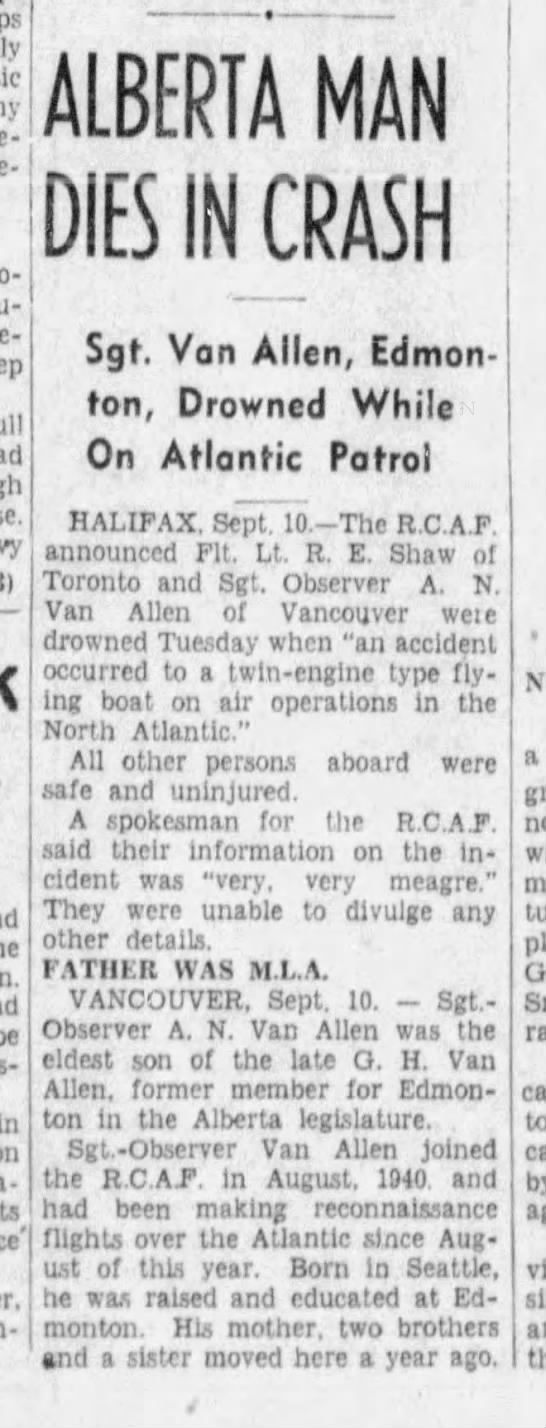

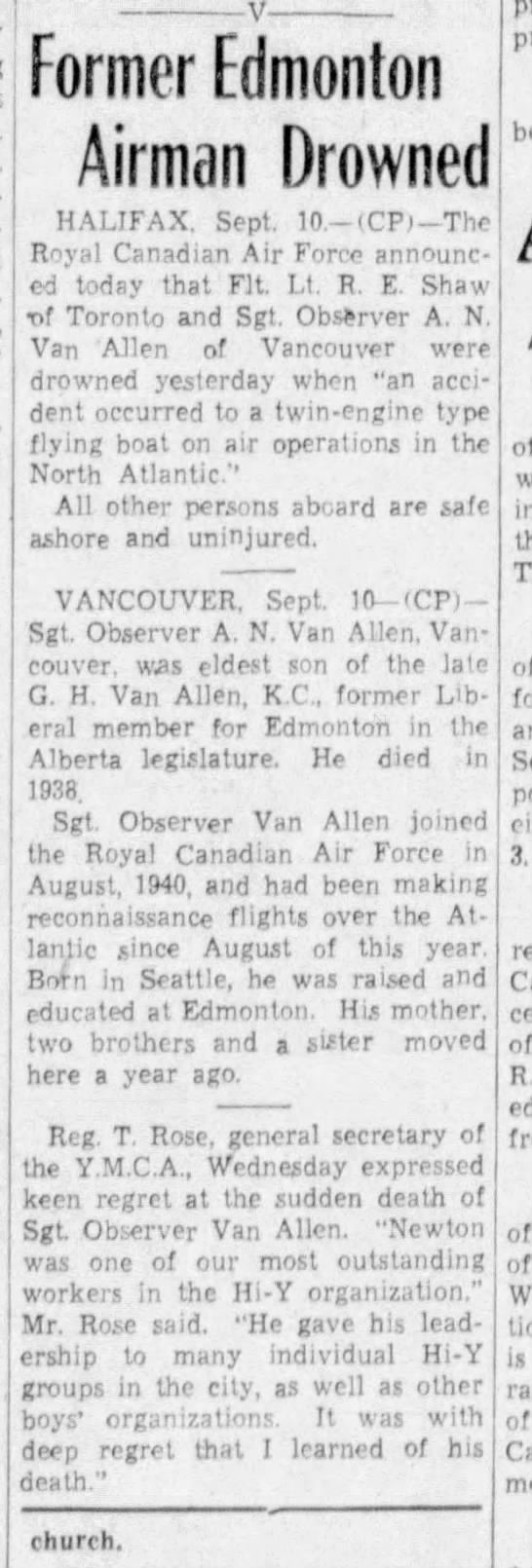

Austin Newton Van Allen, born in Seattle, Washington, was the son of Austin Newton Miller, whereabouts unknown, stepson of George Harold Van Allen (1890-1937), KC, MLA, and Ruby Mabel Traer Van Allen (1898-1992), of Edmonton. He had two half-brothers and a half-sister: Eric William Van Allen, George Traer Van Allen, and Margaret Louis Van Allen. In 1940, Mrs. Van Allen and her children moved to Vancouver, BC. The family attended the United Church.

Known as Newton, he was a student, worked as a rodman for the Dominion Government under the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act during October and November 1939. He had also worked in hotels during the season. His hobbies included photography and radio. He enjoyed a variety of sports, including skiing, swimming, hockey, basketball and golf. He first applied to the RCAF in April 1940. He was accepted August 22, 1940. He stood 5’8” tall and weighed 138 pounds.

Newton’s journey through the BCATP started at No. 1 Manning Depot, Toronto, Ontario August 25, 1940. He was in Dartmouth, NS September 1940, then in Toronto again October 14 to November 3, 1940 at No. 1 ITS, Course 7. “Fine type. Bright and cheerful. Good pilot material. Second recommendation: Air Observer.”

He was in Windsor the next month, returning to Toronto until January 31, 1941. He was sent to No. 5 AOS, Winnipeg, February 3 to April 28, 1941, Course 17. “Doesn’t check calculations but is usually right. GROUND: Fails to take things seriously. 77.6%. Above average. Suffers from an unjustified superiority complex. Drill: 78%.” He was 16th out of 42 in his class.

He was then sent to No. 4 B&G School, Fingal, Ontario, April 28 to June 6, 1941, Course 17. “Is quite young. Has a tendency to do the opposite of what he is told, probably with more service experience should develop into a dependable airman.” He was 26th out of 44 in his class with 75.33%. No. 1 ANS, Rivers, Manitoba was his next posting from June 9 to July 7, 1941, Course 17. “Did well in his groundwork. Average Air Navigator. A bright student. Should develop into a competent observer.” He was 42 out of 111 in his class with 76.2%. “Will make a fair officer after a little more maturing in the service.”

Newton was sent to No. 1 M Depot, Halifax and taken on strength with 116 BR Squadron Dartmouth, NS July 8, 1941.

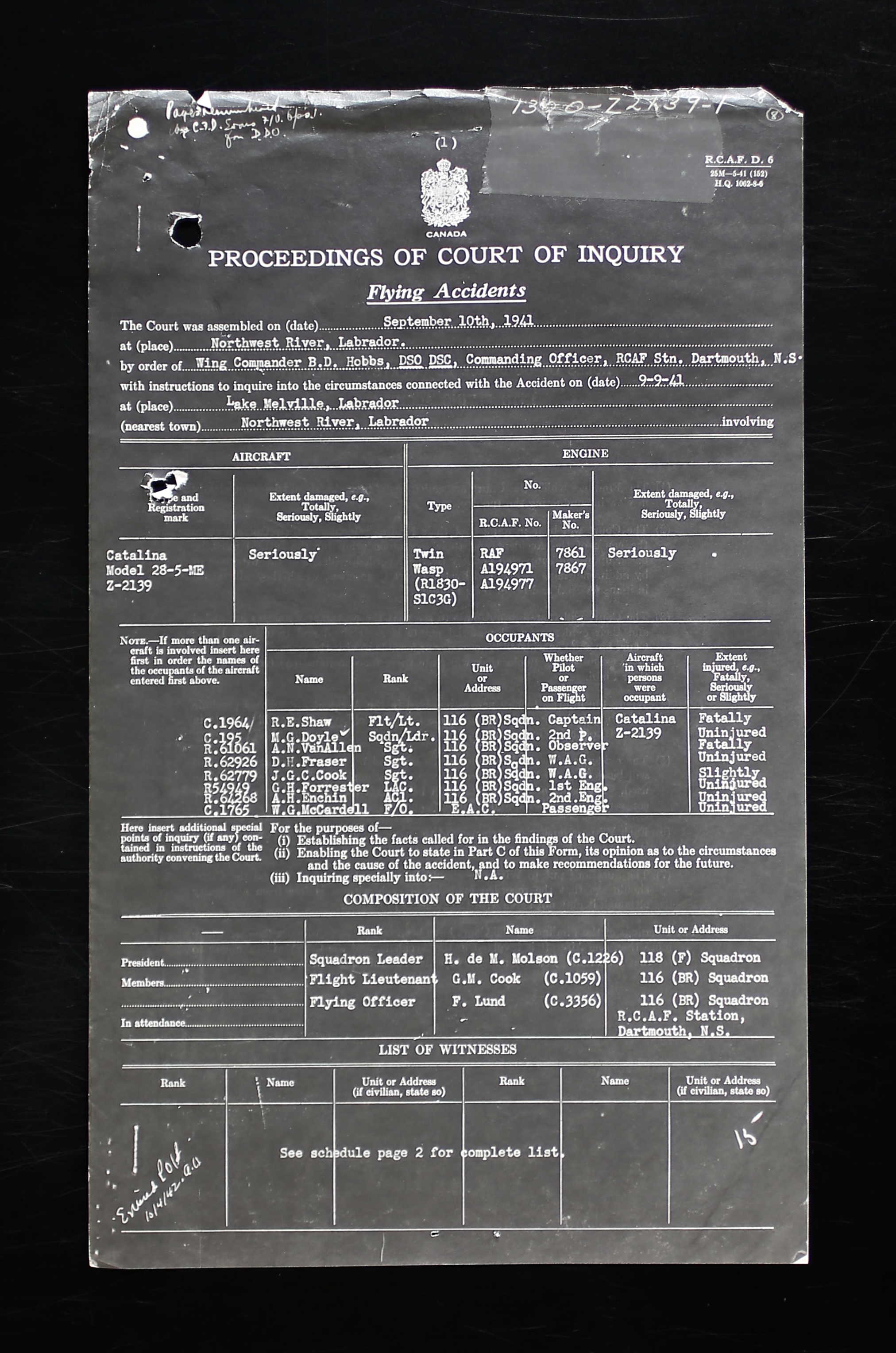

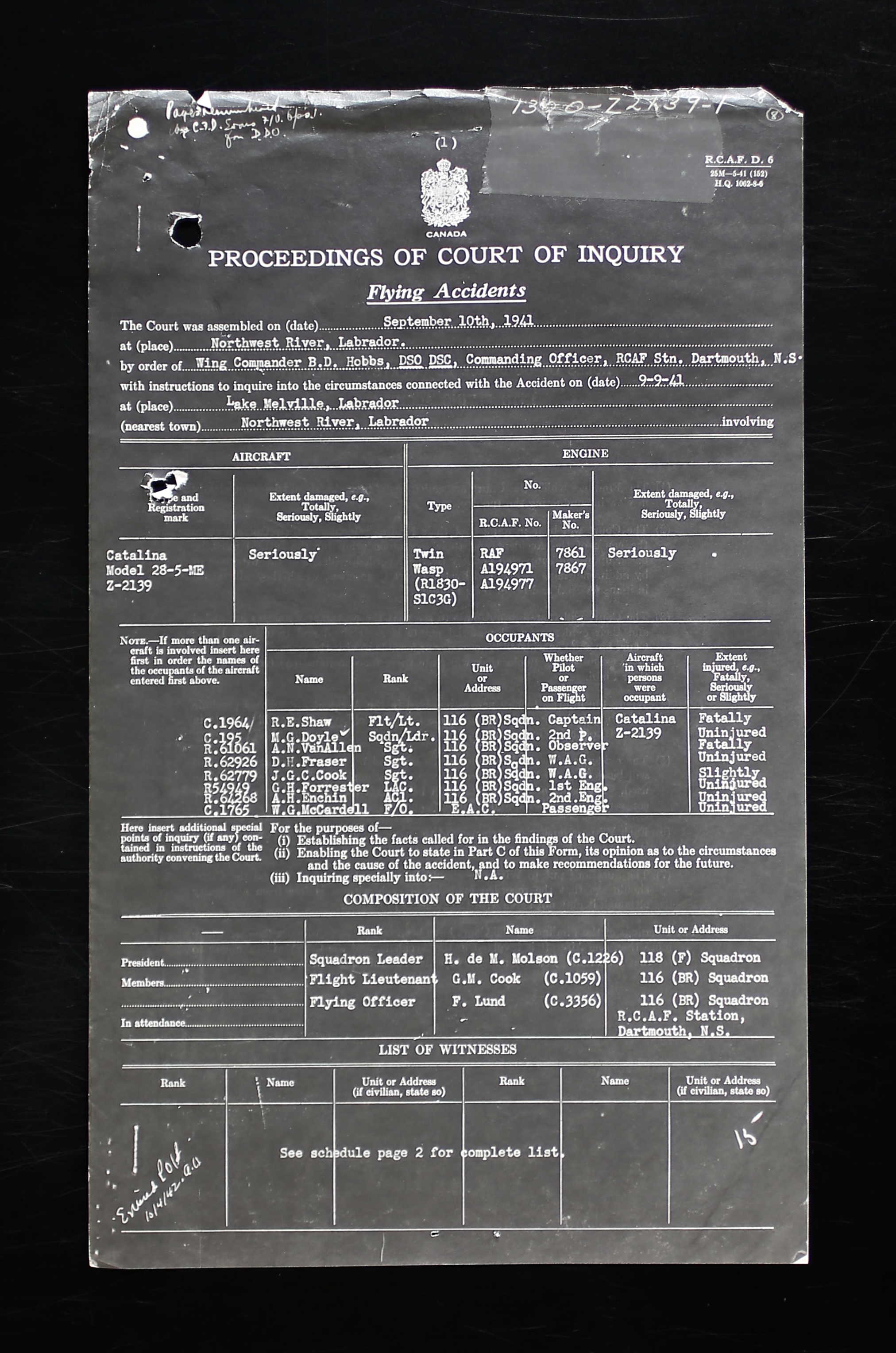

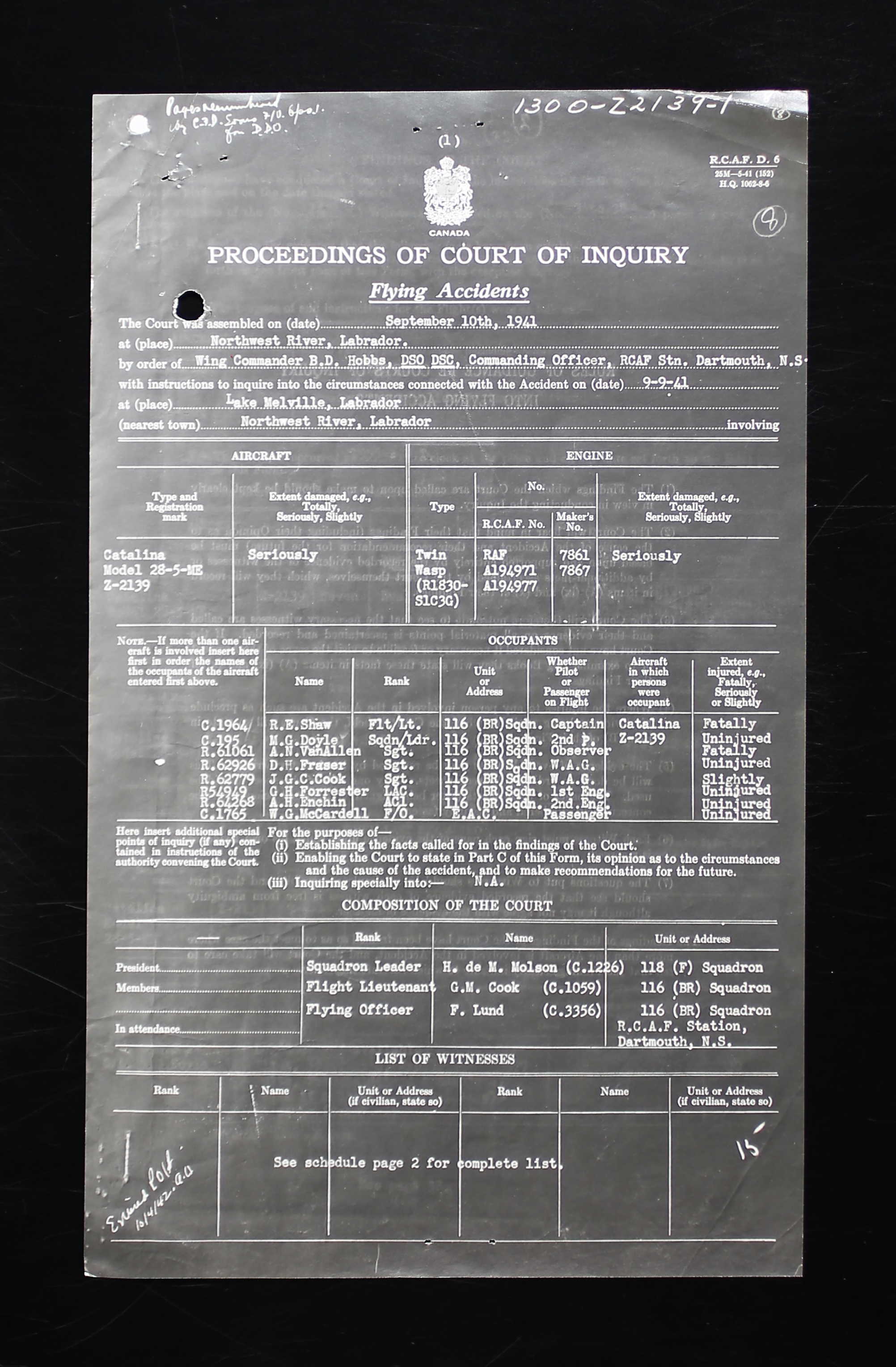

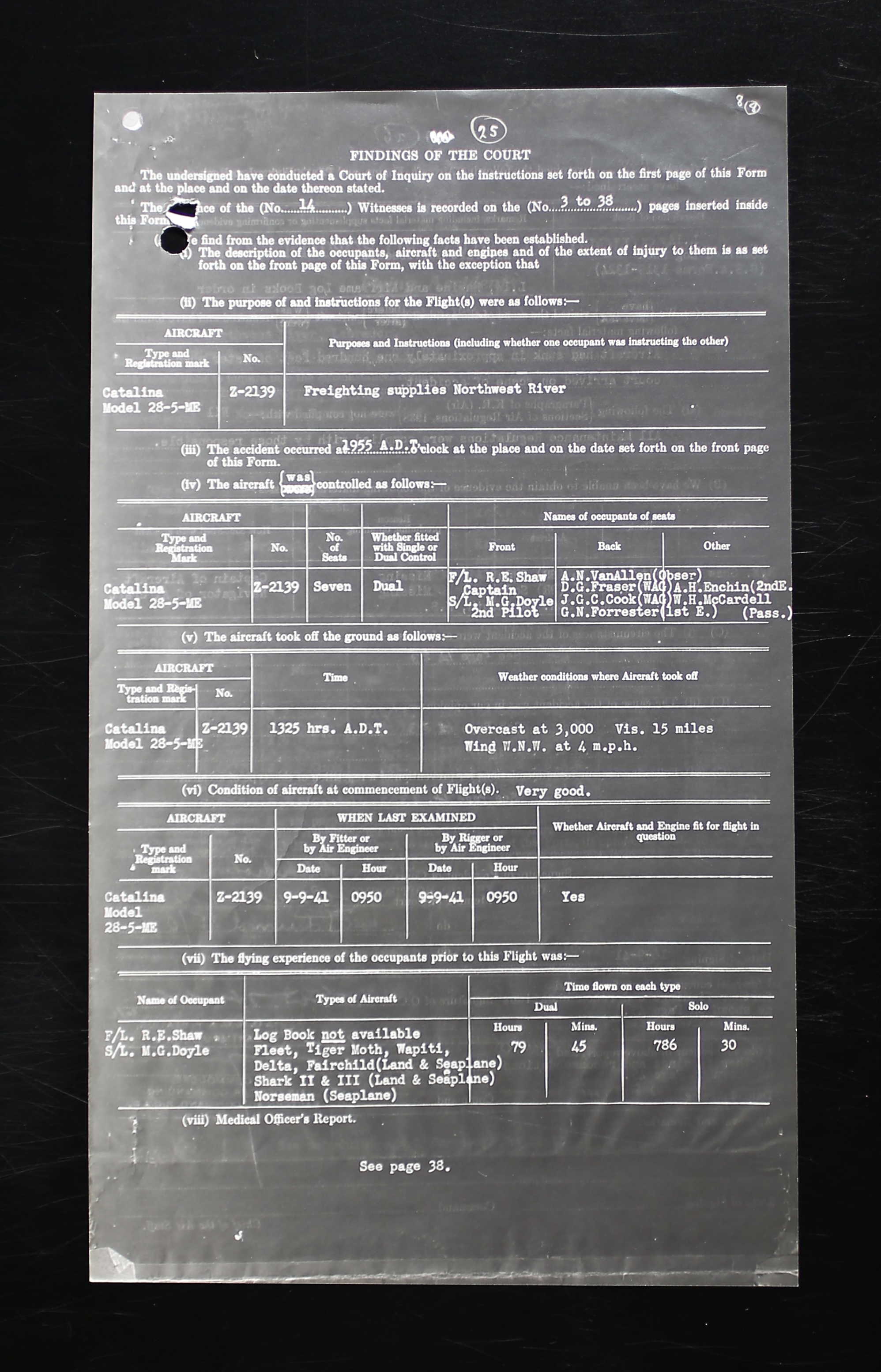

On September 9, 1941, Catalina Z2139 was involved in a flying accident off the Labrador coast when it crashed in the water and sank; cause obscure. Other information: “Place of death: North West River on Labrador Coast; flying accident.” On the Court of Inquiry, place of death was noted as Lake Melville, Labrador.

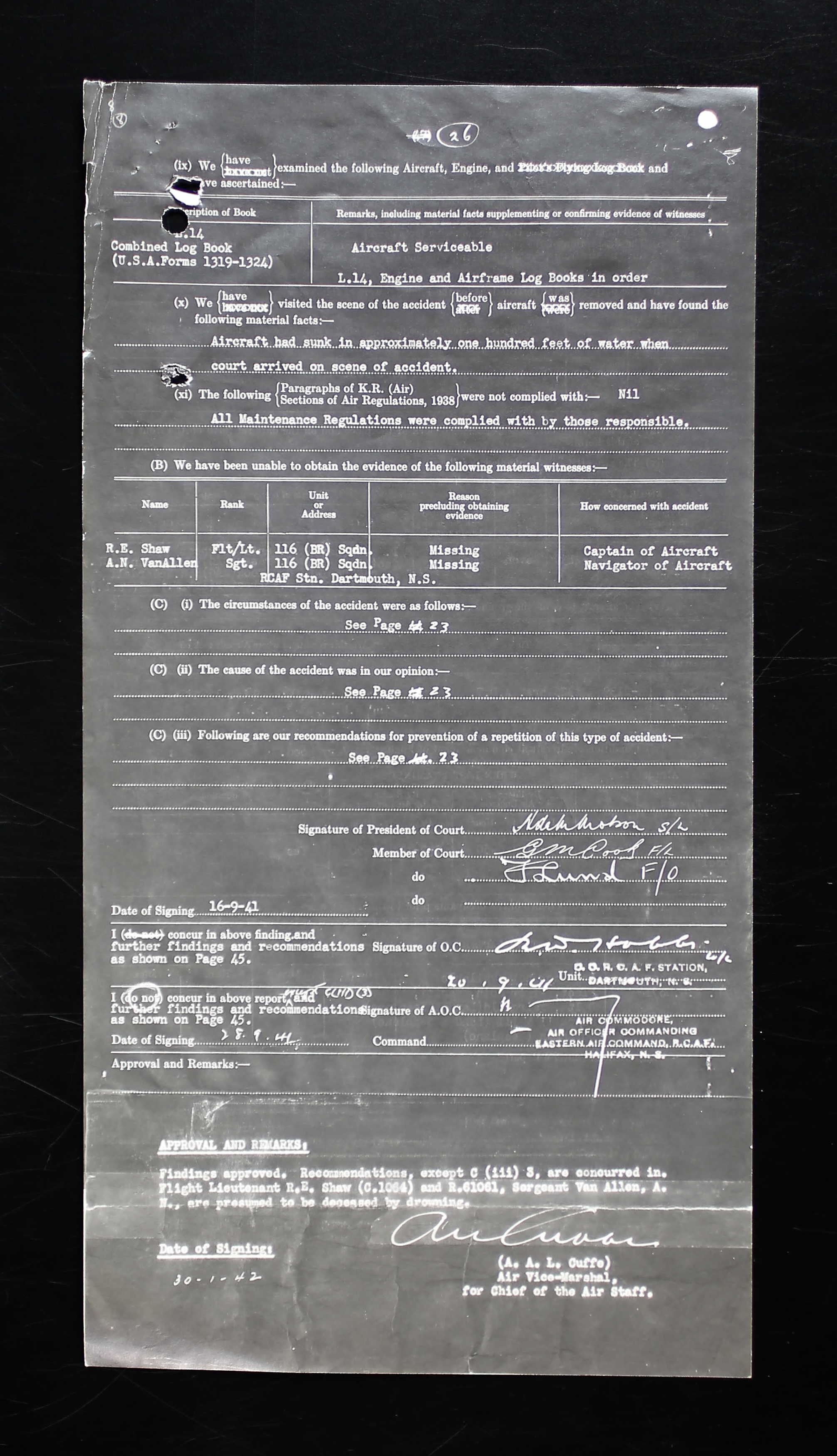

Those aboard were F/L R. E. Shaw, C1964, Captain, S/L M. G. Doyle, C195, 2nd Pilot, Sgt. A. N. Van Allen, R61061, Observer, Sgt. D. H. Fraser, R62926, WAG, Sgt. J. G. C. Cook, R62779, WAG, LAC G. H. Forrester, R54949, 1st Engineer, AC1 A. H. Enchin, R64268, 2nd Engineer, F/O W. G. McCardell, C1765, EAC. Cook was slightly injured, Shaw and Van Allen drowned. The remaining men were uninjured.

From No. 116 Squadron Daily Diary: “September 9, 1941: F/L R. E. Shaw left in 2139 for North West River, Labrador. Had provisions aboard for Department fo Transport. News of 2139 crashing at 1955 hours ADT when landing at North West River. Meagre information is available. F/L Shaw and Sgt Van Allen (observer) missing, presumed drowned. This was later confirmed by syko message from S/L M. G. Doyle (2nd pilot). The aircraft is lying in approximately 60 feet of water. Rapid turn out of most of Squadron personnel to launch 9701 in readiness for take-off at dawn. Next of kin of deceased advised. Court of Inquiry convened. President: S/L Molson, Members F/L G. M. Cook, and F/O F Lund.”

“September 10, 1941: Catalina 9701 proceeded on transportation flight to North West River, Labrador, re: crash of Catalina Aircraft Z2139, passengers: S/L Ferguson, S/L Molson, F/O F. Lund 4:45 hours. Z2138 on transportation flight to North West River, Labrador, passenger: F/L Broderick, 4:15 hours. About 50 men turned out for Wing Parade. All others on duty getting 2138 and 9701 away. The OC W/C Blanchard with F/L Cook and P/O Dobbin left in new Catalina 9701 for North West River, taking members of the Court of Inquiry, S/L Molson, F/O Lund and Medical Officer S/L Ferguson to the scene of the crash of Z2139, departed Dartmouth 0830 hours. 1145 hours, F/L Small with Flying Officer Schlacks took 2138 to North West River with blankets, clothing and Department of Transport food supplies. 2140 standing by for W/C Costello, possibly to go also to North West River. Next of kin of uninjured personnel advised. At 1330 hours, statement to press released by CO of the station. Advised Botwood to send F/L Shaw's clothing back to Dartmouth. The CEO was consulted first. F/O A. B. Whitely, armament officer reported. he is to be on the committee of adjustment for F/L Shaw. Secured personal belongings. F/O Colthurst on committee for Sergeant Van Allen. Clothing, etc., placed in stores and inventoried.” [NOTE: Schlacks was killed in Catalina Z2140 in May 1942 when the depth charges from his aircraft exploded. See link below for more information.]

“September 11, 1941: The OC W/C Blanchard landed 9701 at North West River 1255 hours. Very fast trip. F/L Small landed 2138 at North West River 1620 hours, also fast time….Letters of sympathy written to next of kin of F/L Shaw and Sgt Van Allen. Clothing and effects of each of the above collected and inventoried.”

“September 12, 1941: 9701 returned from North West River, passengers S/L Doyle, S/L Ferguson, S/L Molson, and F/O F. Lund….The OC W/C Blanchard in Catalina 9701 and F/L Small in Catalina 2138 returned from Labrador with members of Court of Inquiry and survivors of 2139 crash.”

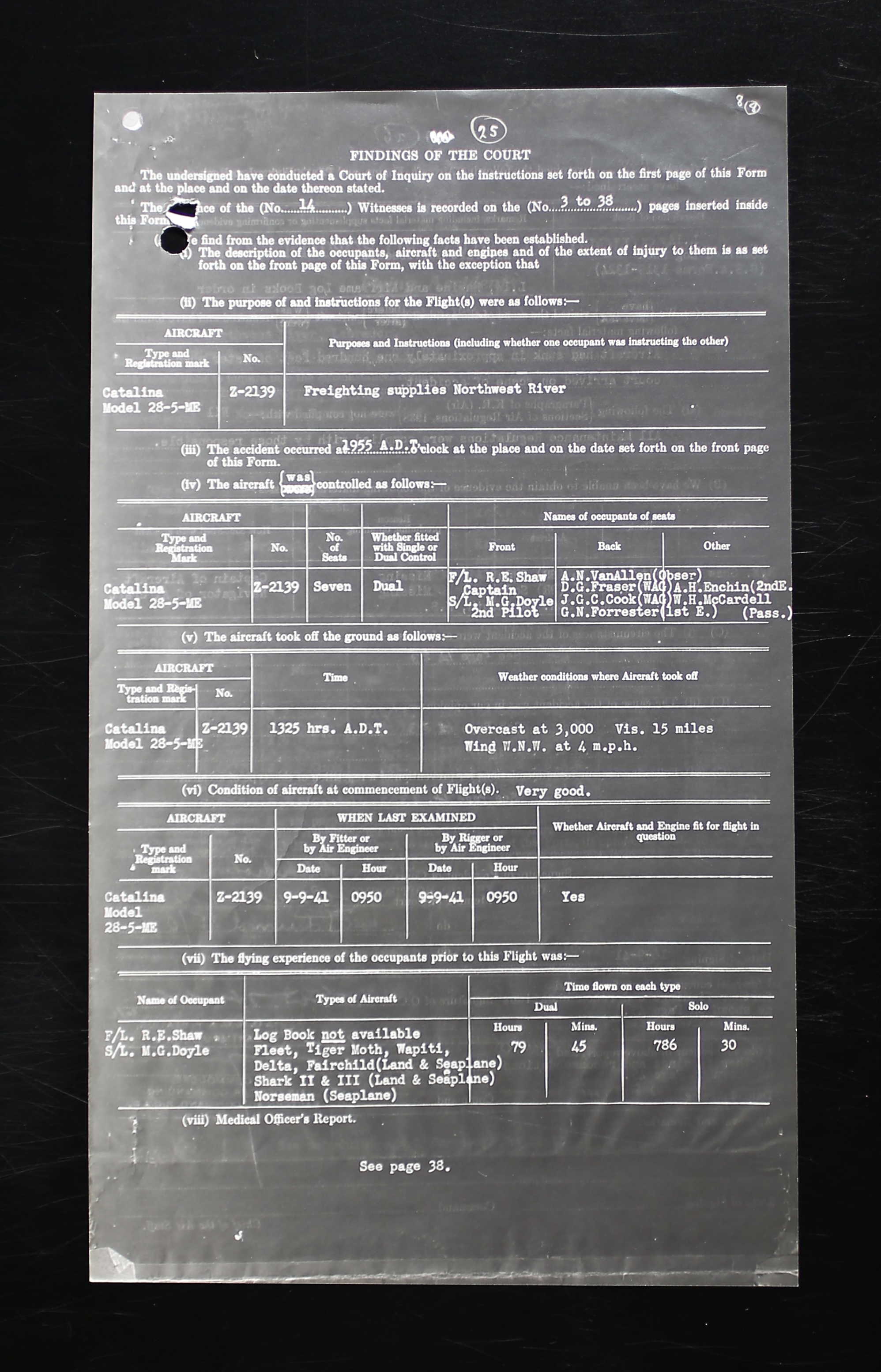

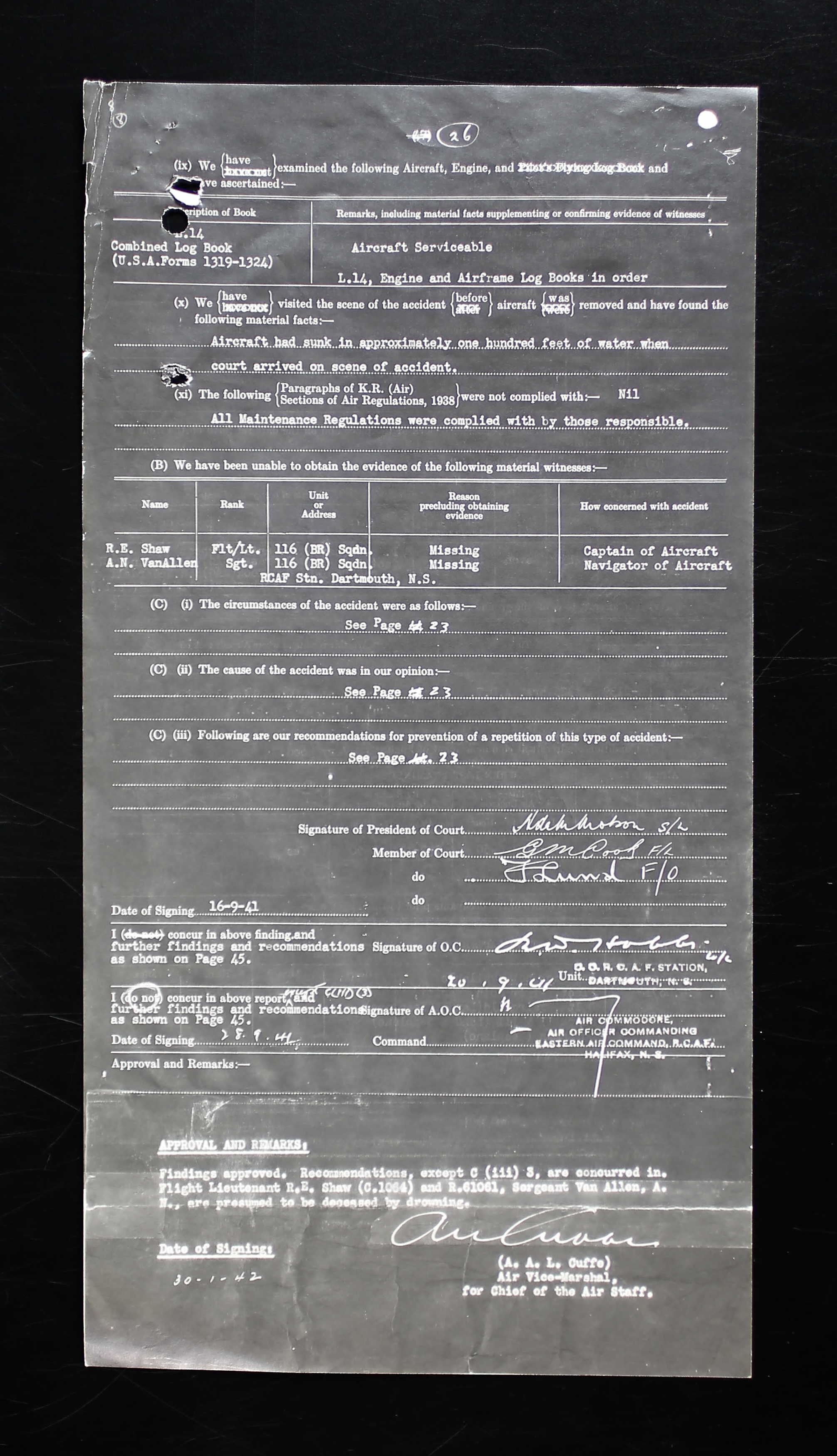

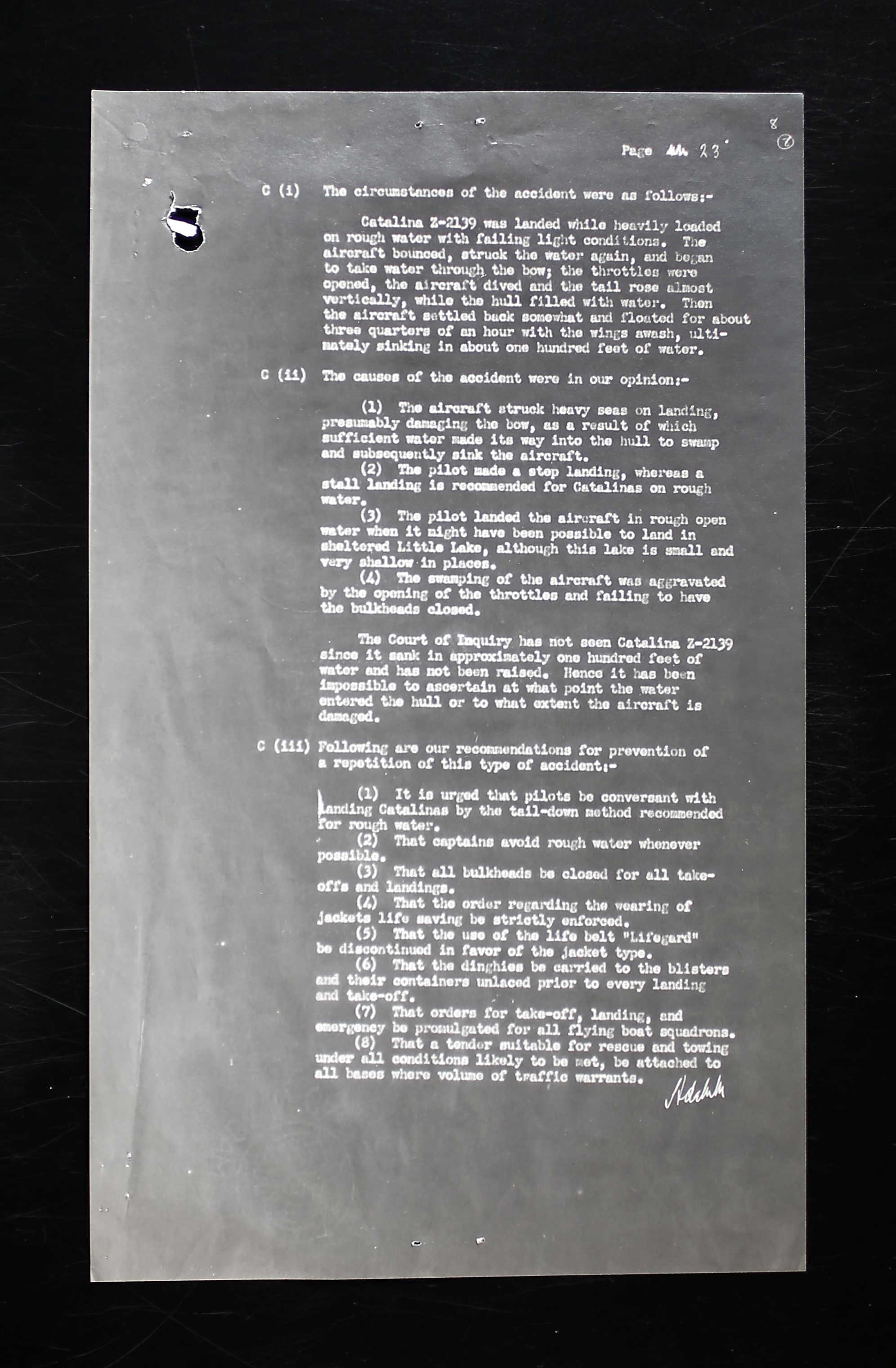

Catalina Z2139 Court of Inquiry [Microfiche C5939, Image 807] began on September 10, 1941, at North West River, Labrador, ordered by W/C B. D. Hobbs, DSO, SFC, Commanding Officer, RCAF Station, Dartmouth, NS. Accident took place at Lake Melville, Labrador on September 9, 1941. Fourteen witnesses were called.

Those aboard Catalina Z2139 were F/L R. E. Shaw, C1964, Captain, S/L M. G. Doyle, C195, 2nd Pilot, Sgt. A. N. Van Allen, R61061, Observer, Sgt. D. H. Fraser, R62926, WAG, Sgt. J. G. C. Cook, R62779, WAG, LAC G. H. Forrester, R54949, 1st Engineer, AC1 A. H. Enchin, R64268, 2nd Engineer, F/O W. G. McCardell, C1765, EAC. Cook was slightly injured; Shaw and Van Allen were deemed drowned. The remaining men were uninjured.

The FIRST witness, S/L Frank Street Coghill, C289, Assistant Controller, RCAF Station, Dartmouth, NS presented Form Green from EAC Controller at 1957, 8-9-41 ordering one Catalina flying boat to depart from Dartmouth for North West River the morning of September 9th. The number of the Catalina used was Z2139.“

The SECOND witness, W/C Sedley Stewart Blanchard, OC, 116 Squadron, stated, “On receipt of instructions by telephone, from the Assistant Controller of this Station, I detailed a crew to proceed to North West River with food supplies and passengers on September 9th, 1941. F/L Shaw, who had acted as captain of the aircraft sent into North West River on a similar trip the previous week, was again detailed as captain. Sergeant Van Allen, who had acted as navigator on the previous trip to North West River, was detailed as navigator of the aircraft. S/L Doyle who had recently arrived at the squadron was detailed as second pilot. Two engineers and two wireless air gunners were also detailed to the crew. The aircraft was loaded with food which was provided under a standing order from the Department of Transport officials. The aircraft also carried some radio equipment for No. 5 BR attachment, Cartwright, and some spare parts for the bomb loading dinghy at North West River. F/O McCardell went with the aircraft as passenger. Before the flight, the usual entry was made in the flight authorization book and initialed by the captain. Instructions have been issued regarding the wearing of life belts. A memorandum was issued to all captains of aircraft on July 19th, 1941, stating that ‘Captains of aircraft are to ensure that all personnel of their crews wear lifebelts while waterborne or airborne.’ This was repeated in D.R.O. Number 19, July 24th, 1941. The all-up load of the aircraft when it left Dartmouth was subtracting the weight of armament normally carried and that of 60 gallons of gasoline, and adding 1000 pounds for the food order, 100 pounds for the radio and 50 pounds for the extra food carried for the crew, I estimate that the all-up weight of the aircraft upon its departure at this base did not exceed 32,360 pounds. Assuming an average consumption of 60 gallons of gasoline per hour, the aircraft would weigh about 29,560 pounds on landing after a six- and 1/2-hour flight. F/L Shaw was shown as qualified as first pilot (day), on Catalina aircraft.”

The THIRD witness, S/L Michael Guy Doyle, C195 stated, “On September 9th, 1941, I was detailed as second pilot for Catalina Z2139 proceeding from Dartmouth to North West River. F/L Shaw was captain. At approximately 1940 hours, we arrived at North West River. We circled the settlement and proceeded to land. F/L Shaw instructed me to handle pitch controls in place in full fine pitch when he throttled back. I did this at about 15 inches of boost. Although the water where we alighted appeared rough, the aircraft touched down smoothly and remained on the water for some little distance. It then bounced off and came back with considerable jar and the windows in the top of the turret were knocked adrift. Water was noticed coming in the nose section of the aircraft. F/L Shaw then opened the throttle in an attempt to get the aircraft on the step, at the same time starting to turn towards shore. Water then commenced to rush in rapidly and the nose of the aircraft started to sink. Realizing all was not well, I started to open the pilot’s hatch overhead, undoing the hook. Water was so high, I reconsidered, figuring more water would come in the window. A moment later, I opened the hatch and started up through it. The engines were still running at full throttle and because of the proximity of the propellers, I sat back in the seat and waited until the nose of the aircraft was completely immersed and the engines stopped. I then extricated myself and swam to a propeller blade and climbed up a port propeller onto the wing. The other members of the crew were at that time coming out of the port blister. A quick check up of the crew showed F/L Shaw and Sergeant Van Allen not on the aircraft. Two objects appeared ahead of the aircraft and were taken to be F/L Shaw and Sergeant Van Allen. These appeared to be making away from the aircraft. This may have been caused by the aircraft drifting downwind. All personnel on the aircraft shouted to come back. A few seconds later, cries for help were heard. No attempt was made to help or rescue; no one was in a position to do so, some of the survivors being unable to swim, those who could were wet and chilled. No lines were available and it was impossible to get a rubber dinghy for the aircraft was completely immersed as far as the aft end of the blisters, the dinghies are stored in the sleeping compartment. Personnel who were on the aircraft made all attempts to restore warmth by arm swinging and carried on continual shouting towards shore. Shortly, a small speck appeared on the top of the waves, which proved to be Sergeant Appleby with the RCAF outboard dinghy. All survivors were taken off in the dinghy and later transferred to a larger, slower boat. Meantime, a search of the area was carried out in an attempt to locate the two missing crew members. The survivors were then brought ashore and cared for by the Grenfell Mission. Sergeant Appleby, who carried out the rescue of the survivors in a small outboard dinghy, did so under rough water conditions, about an 8-foot swell. He was very efficient, cool and level-headed. He then afterwards reported to me that he procured a linr which floated from the wreckage and attached it to an oar and then tied it to the aircraft to mark the ultimate sinking. This line proved too short and shortly after he procured a longer line and anchored a float in the approximate vicinity. He also reported that several boats had carried on a search of the area to discover the missing crew members; they were not discovered. I flew the aircraft during the trip and had control of the aircraft at various times throughout the trip. As this was my first trip in a Catalina, I noticed nothing abnormal. At the start, the aircraft was heading directly for a gasoline barge but as the aircraft gathered speed, the pilot changed their direction to clear the barge by a good margin. From then on, the take-off was comparatively smooth. On arriving at North West River, the pilot began to lose height over Little Lake. His final approach was made in a northeasterly direction into wind on Lake Melville. On his instructions, I placed the pitch controls in fine as he eased the throttles back to 15 inches boost. On nearing the surface of the water, he eased on a bit more throttle and pulled the nose up. The aircraft touched smoothly at approximately 80 knots and stayed on the water for considerable distance. Light conditions were good but deteriorating. I anticipated a few bounces on landing because the water was quite rough. I had asked if they landed in Little Lake and the pilot’s reply was that Little Lake was quite shallow and on his previous trip, he had landed outside on Lake Melville and taxied back. I do not know if F/L Shaw was injured in landing. I did not attempt to operate any controls other than the pitch on the landing. It appears to me on reconstruction of the details that the throttles had not been opened in an attempt at fast taxiing to shore and all bulkheads closed, the aircraft would not have been sunk. As the aircraft had slowed down considerably, and there did not appear to be any great quantity of water coming in, the opening of the throttles aggravated the situation and filled the entire bow section. The water did not come in top of the turret until the nose submerged. The load and its disposition: full tanks of gasoline, crew of seven, one passenger, full emergency equipment, 8 parachutes, and a large load of general supplies consisting of meat and foodstuffs, weight unknown. The supplies were placed in the navigator’s compartment, mostly on the port side. I do not believe the aircraft struck a log or similar obstruction on landing. The weather conditions at the time of landing were clear, visibility 10 miles, wind northeast about 20 to 25 mph.”

The FOURTH witness, F/O William Henry McCardell, C1765, Administrative Officer EAC, stated, “On September 9th, 1941, I was a passenger on Catalina Z2139 from Dartmouth NS to North West River, Labrador. The trip was uneventful until the landing at North West River, when I moved forward from the blisters to the entrance to the navigator’s compartment. The wind appeared to be across Little Lake and the pilot made a normal approach to land in Lake Melville towards the northeast. The initial contact with the water appeared to be fairly smooth but after a short period, there was a bit of a bump giving a feeling of ballooning and then a shock such as would be experienced by hitting the crest of a wave. It was only then that I noticed that the water was rough. At this point, I noticed water flowing in slowly over the floor of the bomb aimer’s compartment. It seemed to me then that full engine was applied in an endeavour, I believe, either to reach shore or to take off again. This was accompanied by a greatly increased flow of water, and the nose began to sink rapidly. The transmitter fell on the floor, the angle of the fuselage increased rapidly to the vertical, and we were thrown forward as a wall of water poured through the pilot’s bulkhead into the navigator’s compartment. With the other members of the crew, I started to climb up the floor to the blisters. When we were part way up, the aircraft gave another violent lurch, and we were thrown back. With considerable presence of mind, one of the crew opened the blisters, enabling all the personnel in the rear compartment to escape and secure positions on the tail and wings, at which time the machine settled to a nearly level position, slowly submerging until it came to rest with the wings partly underwater. At this stage, we had a moment to take stock of personnel, and it was noticed that F/L Shaw and Sergeant Van Allen were missing. About 15 minutes later, Sergeant Appleby arrived with an outboard dinghy and with difficulty, took the crew aboard and transferred us to larger boat which had meanwhile arrived and which we then directed in a sweep search of the area. At least three other boats participated in the search. Excellent work was done by Sergeant Appleby in rescuing the crew and organizing the boats from the settlement in search for the missing pair. The observer, Sergeant Van Allen was wearing a ‘Lifegard’; S/L Doyle was wearing a jacket type. I noticed one other member of the crew putting on one of the jacket type just prior to the flooding of the navigator’s compartment. I did not see F/L Shaw or Sergeant Van Allen leave the aircraft. I vaguely wondered why the landing was made so far out.”

The FIFTH witness, LAC Gerald Nelson Forrester, R54949, Aero Engine Mechanic, stated, “On September 9th, 1941, I was first engineer on Catalina Z2139 for the flight between Dartmouth and North West River. The take-off seemed quite normal and the trip uneventful until the landing. I handled the controls for both take-off and the landing. On the approach, all the instruments were normal. We leveled off and I could feel the aircraft clipping the tops of the waves and what seemed a normal step landing. We had started to slow down when the nose went up steeply and the aircraft left the water. It fell back in with an impact that went through the aircraft. It seemed to settle slowly and for a moment was almost still. Then the pilot opened the throttles and the aircraft shuddered. Water was going by my windows in such quantity that I couldn't open them to see if anything was wrong. Then I saw the crew in the navigator’s compartment going to the rear, so I got down and started back also. I had reached the central bulkhead when the aircraft dived and the tail rose almost vertically. We were thrown back but climbed up again to the blisters and it seemed as if our weight helped to bring the tail down. The water followed us with a rush. I unlocked the port blister and Sergeant Cook opened it. We helped F/O McArdle out. S/L Doyle was on the wing, and he shouted for us to get a dinghy, but we could not for the water was up to the top of the bulkhead door and the dinghies were secured under the bunks. We were then climbing out on the wing. I saw two people who I think were F/L Shaw and Sergeant Van Allen swimming about 20 yards ahead of the aircraft. They were calling to us to leave the aircraft and a short time after we heard calls for help. The water was so cold that none of us were in a position to help. The temperature of the water was afterwards taken, and it turned out to be 46 o F. The first boat to arrive was the RCAF dinghy with Sergeant Appleby. All six of us were taken aboard and he transferred us a few minutes later to a larger boat. We circled the aircraft twice searching for the two missing men, then went to shore without attempting to tow the aircraft because some of the survivors were badly chilled. Sergeant Appleby is, in my opinion, to be highly commended in carrying out the rescue at great personal risk, his small boat being definitely unsuited for such a sea. I do not think that the aircraft struck a log or another object because of the nature of the shock that went through the aircraft. All of us lost personal effects. I am completely satisfied that the engines functioned normally until immersed in water.”

The SIXTH witness, Sgt John Gustav Charles Cook, WAG, stated, “on September 9th, 1941, I was second wireless operator on Catalina Z2139 during the flight from Dartmouth to North West River. I helped stow the cargo before take-off. The trip was uneventful. During the approach, on orders from the captain, I moved to a position beside the navigator’s table. We noticed there was a rough sea and we were braced for the landing. The aircraft touched the water smoothly and stayed on for approximately 2 seconds. Then it left the water, the nose seemed to drop in the aircraft hit the water again well forward with a severe impact. Water began to trickle in the forward compartment from both the turret and the floor. The pilot opened the throttles and water began to rush in heavily. There appeared to be danger, so we grabbed our life belts and headed for the blisters. I saw Sergeant Van Allen reach for the emergency exit in the navigator’s compartment. By the time we got into the engineer’s compartment, the aircraft gave a lurch and the tail rose sharply. This caused F/O McArdell to fall back against the bulkhead between the engineer’s and the sleeping compartments. LAC Forrester got down from the engineer seat and unlocked support blister, which I opened. Then we proceeded out on to the wings, at this time I saw two people in the water ahead of the aircraft approximately 10 or 15 yards. One of them yelled to us to leave the aircraft. They appeared to drift away from us and soon cries for help were heard. Later, Sergeant Appleby arrived with the dinghy and took us aboard and to another boat. Before he got there, we had taken off all excess clothing in case we had to swim; It was washed overboard by waves that could occasionally cover the aircraft up to halfway up the tail. I estimate the weight of the supplies aboard between 800 to 1000 pounds. S/L Doyle was wearing a Mae West, Sergeant Van Allen a Lifegard, LAC Forrester a Lifegard, and I grabbed my Mae West on the way out. Not to my knowledge is there any procedure laid down for takeoffs and landings. I do not believe any cases or boxes were touching the skin of the hull. I do not know if the plate covering the bomb aimer's window was locked.”

The SEVENTH witness, AC1 Archie Harry Enchin, R64268, Aero Engine Mechanic, stated, “On September 9th, 1941, I was second engineer on Catalina Z2139 during a flight between Dartmouth and North West River. Up to the time of landing, the flight was routine. At that time, I was standing beside the navigator’s table next to the pilot’s compartment. We made a normal step landing, ran along the water for a way, bounced off a high wave, then hit the water with the nose low, at this point the aircraft seemed stalled and to settle into the water. While the aircraft was in this position, the pilot opened the throttles. Water was scooped into the nose of the aircraft and the pilot’s compartment began to fill. The door between the pilot’s compartment in navigator’s was open and I left it open in case the pilots wanted to get out that way. S/L Doyle partly opened his escape hatch; I thought he was having trouble with it and pulled it all the way open. He closed it again. Before I opened S/L Doyle's hatch, Sergeant Van Allen had opened the hatch in the navigator’s compartment. When I turned around, only Sergeant Fraser was in the navigator’s compartment with me. I tried to get out the navigator’s hatch but was able to do so only after the compartment had filled because of the rush of incoming water. When I swam to the surface, I was about 20 feet from the wing and it was all I could do to get on. I cannot say that I saw anyone in the water, but sometime later I heard several cries for help. Presently I was taken off in the dinghy with the others. The aircraft only hit the waves. I think the nose of the aircraft was low when the pilot opened the throttles because the people behind me leaned forward against me. We lost all our personal effects except what we had on.”

The EIGHTH witness, Sgt. Donald Hugh Fraser, WAG, stated, “On September 9th, 1941, I was first wireless air operator on Catalina Z2139 during the trip from Dartmouth to North West River. Prior to the landing, the trip had been uneventful. At the time of landing, I was sitting at the wireless set, I had just sent out a landing signal, a SYKO code at 2235 GMT and was wearing the earphones. My first indication that we had landed was a terrific thud and I had to catch myself from being thrown forward. Then the engines were opened up and the aircraft dived and filled very rapidly. The water was right up to my seat by the time I realized something was wrong. I made my way to the blisters, by the time I reached the bunks, the water was up to the top one. I was the last man to come out of the blisters. I stayed in the hull just after the blisters with F/O McCardell. When I looked around, I saw two people in the water about 50 yards ahead of the aircraft. They were calling for help. They had disappeared before the dinghy arrived and took us to a larger boat. I didn't think that the dinghy was going to be able to reach the aircraft. It disappeared behind the waves continually. Sergeant Appleby did a wonderful job of rescue. I do not think the aircraft hit a log or similar obstruction while landing. No one saved anything but what they were wearing when they were taken aboard the dinghy. F/L Shaw was not wearing a lifebelt. Sergeant Van Allen was wearing a Lifegard.”

The NINTH witness was Sgt. Arthur William Appleby, R53561, Motorboat crewman, HQ Squadron, RCAF Station, Dartmouth, NS on temporary duty at North West River. “On the evening of September 9th, 1941, I made the following entry in the log of Outboard N276: ‘1800 hours - prepared Outboard to tender aircraft arriving 1900. Refuel and standby. Aircraft arrived 1950 hours. Circle and landed in heavy sea, Melville Lake, east of North West River. Observed seas breaking over aircraft's motors, speeded up after settling. Nose appeared to dive with tail in air. Ordered civilian boats to scene and rushed in Outboard. 1955 hours - took six men off aircraft: S/L Doyle, Sergeant Cook, Sergeant Fraser, F/O McCardell, LAC Forrester, AC1 Enchin. Informed two men in water and searched area without success. Transferred survivors to civilian boat and continued search. 2010 hours - return to sinking aircraft and searched the after end for bodies. Nose submerged approximately 10 feet and unable to get down. 2020 hours, quite dark, continued search. 2025 hours, tied rope to tale of aircraft, ordered Hudson Bay boat to make to towards shore. Tow delayed by engine trouble. Aircraft sank starboard wing first 2035 hours and approximately 10 fathoms of water. Tied dinghy oar as marker. Another marker laid in approximate area. Continued search until 2120 hours and too dark to see. Returned North West River and arranged for early morning search for two bodies, F/L Shaw and Sergeant Observer Van Allen. Estimate size of waves: 18 to 20 feet crest to crest, four to five feet high. Wind north by K .25 mile velocity.’ I think this is the best account I can give you as it was entered while it was fresh in my mind. There was a tremendous spray when the aircraft landed which went right over the aircraft particularly when the throttles were opened. I did not see any objects on my way out that might have been swimmers near the aircraft. The aircraft might have been beached if a tow had been started when the first boats arrived if everything had started immediately. There was only one boat here that was heavy enough, the Hudson's Bay company boat, and it had engine trouble.” [NOTE: Arthur William Appleby (1916-2011) “received the British Empire Medal in December 1942 at the investiture at Government House for his heroism in the rescue of six of the eight-man crew of a Catalina flying boat which crashed while landing on September 9, 1941, off the Labrador coast.” He remained with the RCAF after the war, retiring in 1964 with the rank of Squadron Leader. He earned his pilot’s wings, the DFC, serving in Labrador, Europe, India, Canada’s Arctic, Ottawa, Winnipeg, and Washington, DC.]

The TENTH witness, Ranger Valentine Patrick Duff, Newfoundland Rangers: “Around 8:00 PM ADT, September 9th, I saw a plane circling and went up on my roof to watch it land. It touched the water in what seemed a normal way and appeared to lose flying speed. Then I heard him gun the engines, as I thought, to turn and taxi in. There was a big cloud of spray and the tail began to rise. It came to a nearly vertical position, stayed there for 20 or 30 seconds, then settled back a little. I ran down to get a boat and set out for the aircraft. The sea was rough with a short choppy lop. We saw survivors on the wing; they were taken off by the RCAF boat. We cruised around looking for other survivors and picked up a cushion. It was very hard to see because it was getting dark and it was overcast, and we only saw the cushion when about 20 or 30 feet away. Later that night, I got some men and walked along the beach as far as Gibson Cove. We found the aircraft keys on a cork float, a ration tin, an oil tin, and a boat hook.”

The ELEVENTH witness, Mr. Allen Kilburn Bayley, Radio Engineer, Radio Aviation Section, Radio Division, Department of Transport: “At North West River, Labrador, on September 9th, 1941, I heard an aircraft approaching at about 7:30 PM ADT. and went out on the dock to watch it land. It circled as if to land on Little Lake, but to my surprise maintained a higher altitude and landed instead in a north-easterly direction on Lake Melville at approximately the point marked X on the chart appended to this report as exhibit A. The approach seemed normal until the aircraft landed, when there was a tremendous splash, and then another splash half as large. The aircraft slowed down and almost immediately I saw flashes from both exhausts and heard a loud roar from the engines. At this point, for an instant, I got the impression that the pilot had got control of the situation and that he was preparing to taxi. Immediately following this impression, I saw something which appeared to be a wing rising out of the water and standing almost erect. On studying it for a minute or so I could see from its structure it was the tail. It was only about half a minute from the time it was obvious that the ship was in trouble that I heard the RCAF dinghy with an outboard engine start out and I saw it go out with one man in it in a rough sea, with rollers which hid it from view between the swells. By the time the boat reached the aircraft, the combined overcast and dusk made it impossible to see whether any people were outside the aircraft or not. That darkness came very quickly. By about 8:28 ADT, it was no longer possible to distinguish anything in the darkness. The breakers on Lake Melville were about 5 to 10 feet high in the wind approximately 20 to 25 mph. I saw six people landed from the aircraft.”

The TWELFTH witness, Mr. Asmund Berg Holand, Assistant Superintendent Engineer by the Department of Transport: “At North West River, Labrador on September 9th, 1941, I heard an aircraft come in and shortly afterwards Mr. Sidney Bird of McNamara Construction Company Ltd. came to our quarters saying that he thought the aircraft was in trouble. We ran down to the dock, asked a local boat owner to take us out and set out with two RCAF airman, and two or three natives. As we reached the dock, Sergeant Appleby was already on his way out in an outboard dinghy. When we arrived near the aircraft, Sergeant Appleby had picked up the survivors which he transferred to our boat which was considerably larger. We were told that there were two missing, so we circled for a possibly half an hour and then discussed trying to tow the aircraft. As the boat was low on gasoline and the survivors were chilled, I told the owner to return with the idea of landing the survivors, refueling and then returning to the aircraft to attempt towing it ashore. However, when we had done this and got back, the aircraft had sunk and Sergeant Appleby was circling the spot in the dinghy. We dropped an anchor to a log indicating the approximate position of the aircraft. I should like to mention that I thought the actions of Sergeant Appleby to be worth particular mention considering the very rough sea, for doing everything possible from the time he arrived until after the aircraft had sunk. The sea conditions were very rough on Lake Melville. We were trying to get a boat to go to Hamilton River and they didn't think it advisable.”

The FOURTEENTH witness, S/L Ewart Adair Fergusson, Senior Medical Officer, RCAF Station, Dartmouth, NS: “On September 10th, 1941, I proceeded by air to North West River, Labrador, to visit the scene of the crash of aircraft Catalina Z2139. On arrival, I examined the survivors and found that, with the exception of Sergeant Cook, who was suffering from contusion of the left arm, all the members of the crew were uninjured. I believe that the two missing men, F/L Shaw and Sergeant Van Allen are drowned, although it is possible that these members of the crew sustained injuries in getting out of the aircraft, which would incapacitate them so that they would be unable to keep afloat for any length of time.”

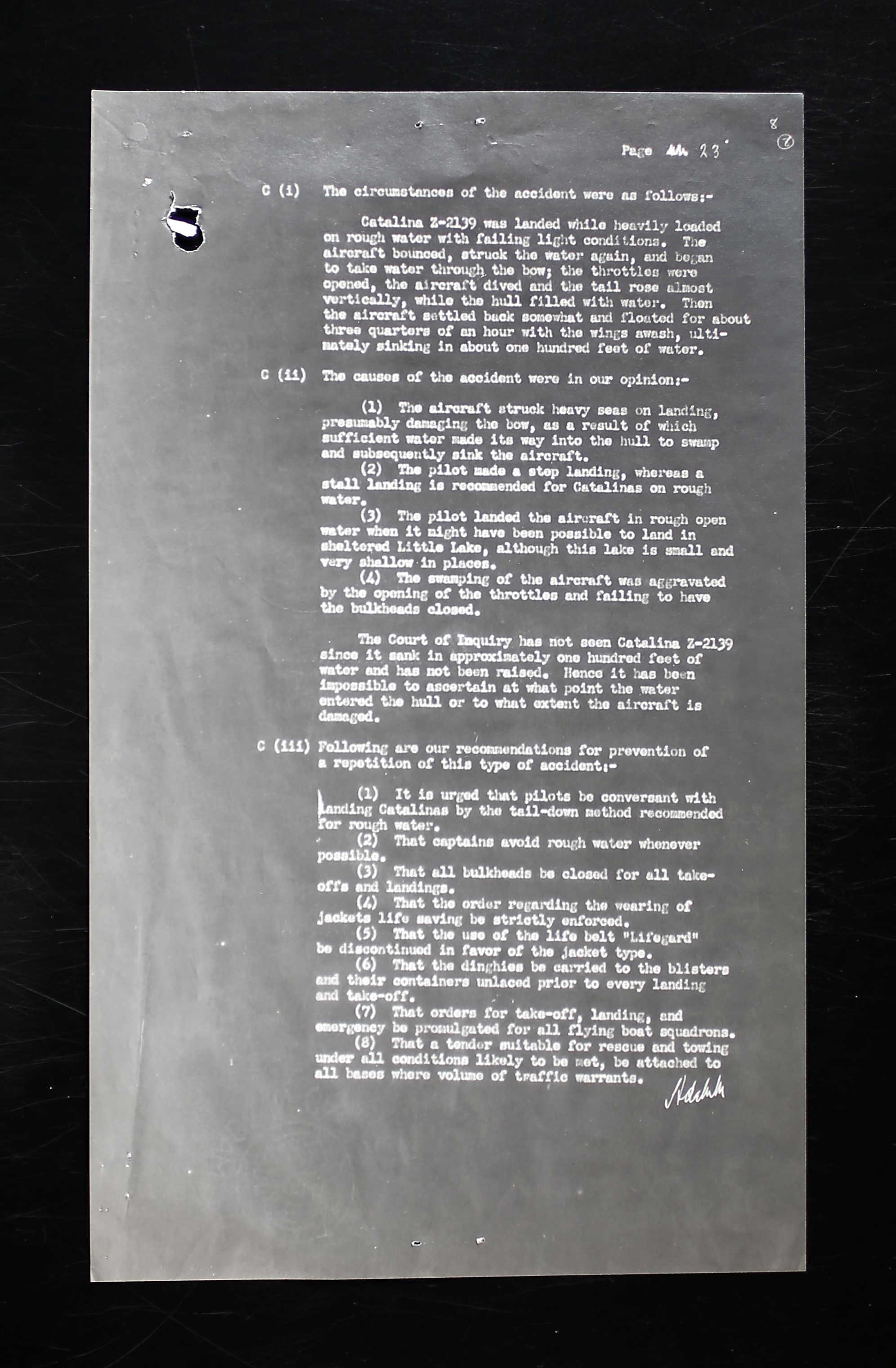

CIRCUMSTANCES OF ACCIDENT: “Catalina Z2139 was landed while heavily loaded on rough water with failing light conditions. The aircraft bounced, struck the water again, and began to take water through the bow; The throttles were opened, the aircraft dived and the tail rose almost vertically, while the hull filled with water. Then the aircraft settled back somewhat and floated for about 3/4 of an hour with the wings of wash, ultimately sinking in about 100 feet of water. CAUSE: the aircraft struck heavy seas on landing, presumably damaging the bow, as a result of which sufficient water made its way into the hull to swamp and subsequently sink the aircraft. The pilot made a step landing, whereas a stall landing is recommended for Catalinas on rough water. The pilot landed the aircraft in rough open water when it might have been possible to land in sheltered Little Lake, although this lake is small and very shallow in places. The swamping of the aircraft was aggravated by the opening of the throttles and failing to have the bulkheads closed. The Court of Inquiry has not seen Catalina Z2139 since it sank in approximately 100 feet of water and has not been raised. Hence it has been impossible to ascertain at what point the water entered the hull or to what extent the aircraft is damaged. RECOMMENDATIONS: It is urged that pilots be conversant with landing Catalinas by the tail down method recommended for rough water. That captains avoid rough water whenever possible. That all bulkheads be closed for all takeoffs and landings. That the order regarding the wearing of jackets lifesaving be strictly enforced. That the use of the lifebelt ‘Lifegard’ be discontinued in favor of the jacket type. That the dinghies be carried to the blisters and their containers unlaced prior to every landing and takeoff. That orders for takeoff, landing, and emergency be promulgated for all flying boat sequences. That a tender suitable for rescue and towing under all conditions likely to be met be attached to all bases where volume of traffic warrants.” FURTHER FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS: “F/L Shaw and Sergeant Van Allen must be presumed lost by drowning owing to the distance from shore, the roughness of the sea, the extreme coolness of the water and the evidence of eye witnesses. There last apparently may be attributed to the lack of use of adequate life belts. Failure to close the bulkheads was partially responsible for the inaccessibility of the dinghies. The rescue efforts of Sergeant Appleby demonstrated the highest degree of courage, calm decision, and seamanship; And under the circumstances were as thorough as possible. It is recommended that recognition be made of the courage and ability shown by Sergeant Appleby in these rescue operations by promoting him to Flight Sergeant (paid) with a view to encouraging similar traits in all personnel. It is believed that Sergeant Van Allen was wearing a. ‘Lifegard’ yet he was not afloat. Life belts which incorporate mechanical operation may prove useless to the where in an emergency because of possible injuries. Also, the ‘Lifegard’ being a waist type, does not give the correct posture to the body when in the water, in consequence an injured wearer might easily be drowned. The ability of the ‘Lifegard’ to support a person in heavy flying clothing is questioned. Therefore, it is strongly recommended that the use of the lifebelt known as ‘Lifegard’ be discontinued in the service in favor of the jacket type. It is recommended that the private losses incurred by personnel due to the accident be borne by public expense.”

January 28, 1942: “This flying accident is to be brought to the attention of all pilots as an example of the folly of attempting to make a fast step landing on a rough sea under conditions which favoured a slow ‘tail-down’ landing. This accident is another example of the necessity for enforcing the wearing of adequate lifebelts by all crew members of waterborne aircraft whilst taxying, taking off, and landing. The question of adequacy of the ‘lifeguard’ lifebelt is being further dealt with by this Headquarters. It will be noted that the AOC, EAC, has recommended that the lifebelt ‘Life-gard’ be withdrawn from service, as being unsatisfactory.”

February 4, 1942: “Life-gard safety belts are not authorized to be carried in Aircraft…authorized for issue on the basis of one per motor boat crewman and three per 1 E seaplane and flying boat for use of aeroengine and airframe mechanics while proceeding to and while servicing, mooring, and performing general work on Aircraft on water.”

February 5th, 1942: “The ‘Life-gard’ is only to be used by motor boat crewmen and aero engine and airframe mechanics while servicing aircraft on water.”

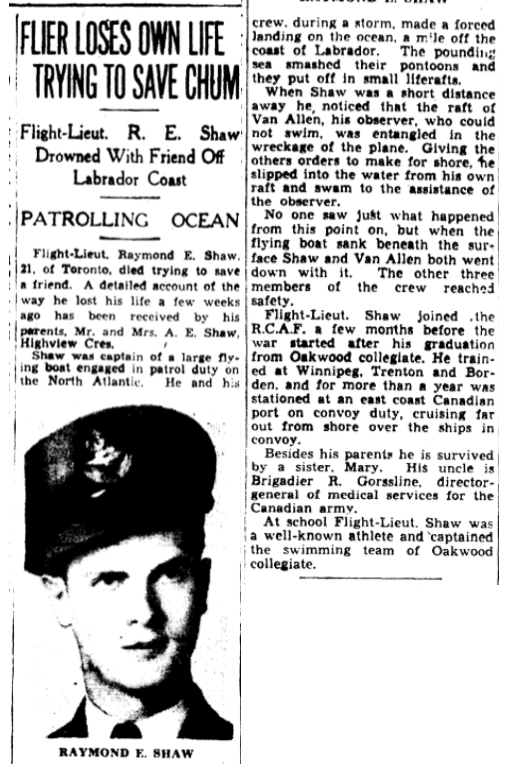

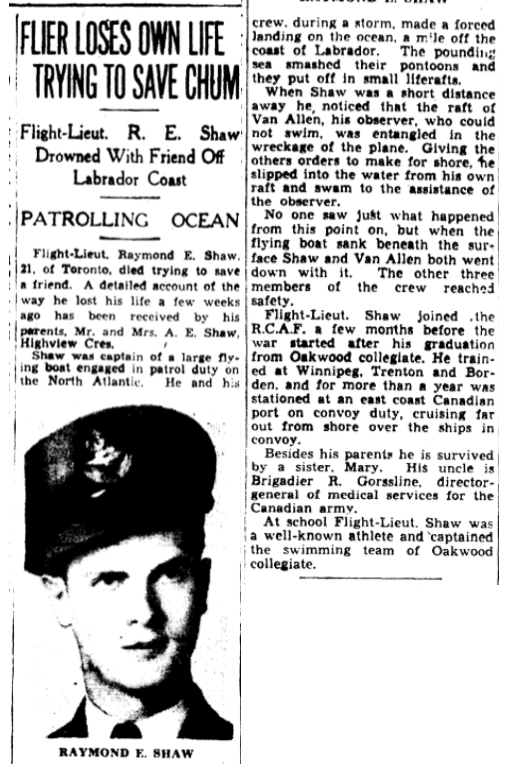

According to an article in the Toronto Star in connection to Raymond Shaw, dated October 1941, “A detailed account of the way he lost his life a few weeks ago has been received by his parents... Shaw was captain of a large flying boat engaged in patrol duty on the North Atlantic. He and his crew, during a storm, made a forced landing on the ocean, miles off the coast of Labrador. The pounding seas smashed their pontoons and they put off in small life rafts. When Shaw was a short distance away, he noticed that the raft of Van Allen, his observer, who could not swim, was entangled in the wreckage of the plane. Giving the others orders to make for shore, he slipped into the water from his own raft and swim to the assistance of the observer. No one saw just what happened from this point on, but when the flying boat sank beneath the surface, Shaw and Van Allen both went down with it. The other three members of the crew reached safety.”

Newton is remembered on the Ottawa Memorial as well as on his family’s headstone at the Edmonton Municipal Cemetery, at Hanes Cemetery, Dundas, Ontario and his name is on the Joint Services Cemetery in Goose Bay, Labrador. The engraving says, “These brave men were lost on September 9, 1941 while transporting supplies from 116 BR Squadron, Dartmouth, to North West River. Their bodies were never recovered from the nearby waters of Lake Melville. May they rest in peace.”

LINKS: